The Savoias of the Balearic Islands

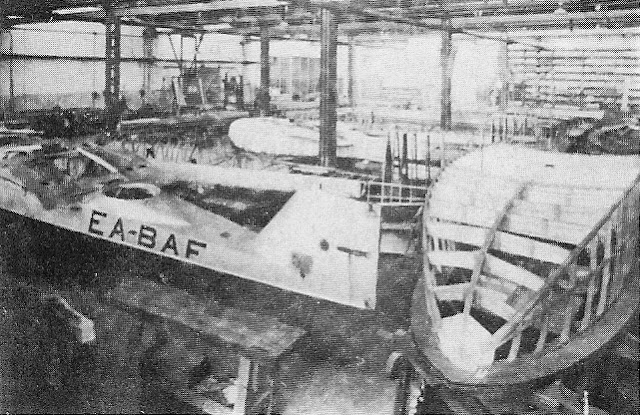

In the summer of 1936, during the early phase of the Spanish Civil War, the loyalist and rebel forces struggled for the control of the Balearic archipelago. Because of the nature of the area of operation, the fight became a confrontation of air and naval forces, in which the Savoia S.62 seaplanes of the Spanish Aeronáutica Naval played a prominent role. (Above, there is a picture of a newly built Spanish S.62, that has just come out of the arsenal of Barcelona).

The Aeronáutica Naval had begun to reequip with Italian seaplanes at the beginning of the 1920's, while the country was engaged in the war in Morocco. In 1929, the works of Barcelona began building the S.62 armed reconnaissance seaplanes under license from SIAI Savoia.

The Aeronáutica Naval had begun to reequip with Italian seaplanes at the beginning of the 1920's, while the country was engaged in the war in Morocco. In 1929, the works of Barcelona began building the S.62 armed reconnaissance seaplanes under license from SIAI Savoia.

|

| S.62's being built, in the works of the Aeronáutica Naval of Barcelona. |

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the majority of the officers and the troops of the Aeronáutica Naval sided with the Republic (which is interesting, since the Air Arm of the Spanish Navy had been established by a royal decree, on September 15, 1917); and the Spanish naval seaplanes spearheaded the invasion force that attempted to regain full control of the Baleares on the part of the loyalist forces.

|

| An S.62 in the auxiliary naval air base of Marin, in 1933 |

The following is a translation of a chapter of a 1981 Italian book byAngelo Emiliani: "Italiani nell'Aviazione Repubblicana Spagnola," that is, "Italians in the Spanish Republican Air Force," published by Edizioni Aeronautiche Italiane srl. The chapter was entitled: "The Catalan Expedition to the Balearic Islands."

I thought it was interesting, because it dealt with an almost ignored episode of aviation history, in which the aircraft involved were almost exclusively seaplanes, and almost all of Italian origin. And today is July 18.

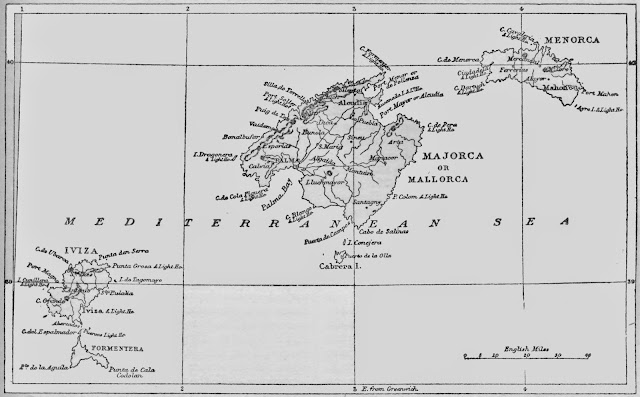

The Spanish government of the Second Republic had reestablished the Catalan "Generalidad," that is, the autonomous government of Catalonia. Nevertheless, it is not clear to me on what basis the Catalan administration had the authority to organize an invasion force that entailed the use of the military assets of the Spanish central government (the author of the book takes quite a bit for granted, and does not explain it). Any clarification would be welcome. I hope you will be able to follow the action on the charts I have included in the translation; and your comments, as usual, will be greatly appreciated. Thanks,

L. Pavese

THE CATALAN EXPEDITION TO THE BALEARIC ISLANDS.

(di Angelo Emiliani. Translated by L. Pavese)

The project of an expedition to Majorca, that had fallen under the control of the seditious forces, matured in the military headquarter of Barcelona at the end of July 1936.

The military and especially the air arm, who knew the Balearic Islands very well, were aware of the strategic importance of the Mediterranean archipelago. The island of Majorca in the hands of the enemies of the Republic constituted a real threat, positioned right off the Catalan coast.

From an aerial warfare point of view, the island could be compared to a giant unsinkable aircraft carrier, stationed within range of the important Catalan cities along the coast and inland alike. A few months later, the heavy aerial bombardment of Barcelona (March 18, 1937) by the Italian Legionnaire Air Force, and the bombings of Valencia, Tarragona, Gandia, Alicante and Sagunto would prove right those who had understood the need to regain complete control of the Balearic islands.

During the brief period in which the Republicans attempted the retaking of the Balearic Islands, the European embassies and capitals wove an intricate diplomatic web. The behavior of the Italians in particular gave rise to some tension. First there was the unrequested deployment of several Italian aircraft, and there followed the arrival in Majorca of Arconovaldo Bonacorsi (1898-1962), a Bolognese Fascist leader, who called himself Conde Rossi (Count Rossi) and claimed to be a personal friend of Benito Mussolini. The “Red Count” took over the de facto defense of the major Balearic island, and removed from power the local authorities accusing them of incompetence.

During the brief period in which the Republicans attempted the retaking of the Balearic Islands, the European embassies and capitals wove an intricate diplomatic web. The behavior of the Italians in particular gave rise to some tension. First there was the unrequested deployment of several Italian aircraft, and there followed the arrival in Majorca of Arconovaldo Bonacorsi (1898-1962), a Bolognese Fascist leader, who called himself Conde Rossi (Count Rossi) and claimed to be a personal friend of Benito Mussolini. The “Red Count” took over the de facto defense of the major Balearic island, and removed from power the local authorities accusing them of incompetence.

|

| "The Red Count" in Majorca |

By then, the Italian hegemonic aims over the Mediterranean Sea were already one of the dominant themes of the Fascist expansionist policy; and less than four years later they would be the motivation of the Italian entry in World War II.

With respect to the Spanish war, Great Britain maintained an ambiguous position, but not when her domination of the seas and her role of guarantor of maritime traffic was threatened. The Britons repeatedly refused to recognize General Franco’s right to extend the war outside Spanish territorial waters, and later they showed great resolve calling for the Convention of Nyon (in September of 1937), officially to deal with the issue of piracy, but in reality to demand that the German and the Italian warships stopped shooting on the freighters heading to the Republican ports.

As far as France was concerned, an enemy base in the Balearic Islands in case of war could be of decisive importance for the safety of the sea routes between Algeria and the mainland. Even the Germans were alarmed by the Italian intervention in Majorca. Notwithstanding the assurances of Italian Foreign Minister Gian Galeazzo Ciano (1903-1944), the German ambassador in Paris, Welczeck, communicated his worries in a telegram to Berlin: “Francisco Franco,” he said, “in a way or another, will favor the Italians in the Mediterranean,” in exchange for the help he had received.

|

| A picture of the Spanish naval air base at Prat, Barcelona, taken by the Italian airship Esperia in 1925 |

It is likely though that neither in Madrid nor in Barcelona there was a real appreciation of the international appetite for the Balearic Islands. Therefore, the expedition organized to attempt the retaking of the archipelago was undertaken for the right reasons, but with totally inadequate plans, relatively weak forces, and a low level of coordination. As a matter of fact, the central government in Madrid considered the operation an useless waste of assets, and was very quick to order an end to the operation, when the tide turned against the Republican forces.

|

| A formation of five Spanish S.62 from Barcelona, in flight before the beginning of the Civil War. |

From an aviation historian point of view, there is an episode that preceded the invasion that is worth remembering.

On July 19, 1936 (two days after the beginning of the rebellion) General Manuel Goded Llopis, one of the leaders of the insurrection, flew to Barcelona from the Mahon Naval Air Base (on the island of Minorca) with five Italian seaplanes Savoia S. 62 (license-built in Spain) to take charge of the revolt.

One of the seaplanes (S-10), flown by pilot and flight instructor Francisco Casals, had remained behind in Palma de Majorca, by now in rebel hands, with engine troubles.

|

| Valencia, 1936. A ground-crew is removing the protection sheath of the four-blade wooden propeller of a naval S.62, number S-18 |

The rebels did not trust the pilot, and one of the first precautions they took was to separate him from his mechanic, and prevent them from getting near the aircraft. But on the island there was no one who could fix the engine, let alone fly the seaplane that remained inoperative, bobbing in the waves in the harbor. Therefore, Casals was finally allowed to work on the engine of the airplane, but under the watchful eye of an armed guard who followed his every movement.

After he managed to restart the engine Casals, with the excuse to test it, began to cause abrupt movements of the aircraft, until the anchor was free from the bottom. Then he put the bow of the craft into the wind and took off, dragging the anchor, still dangling from the long line.

The astonished guard had no time to stop Casals’ maneuver, and once the aircraft was flying he had no choice but accepting his bad luck and end up a prisoner.

When the moment of surprise had passed, the rebels on the shore began to shoot at the airplane that was getting away rapidly towards freedom for the pilot and captivity for his guard.

When the moment of surprise had passed, the rebels on the shore began to shoot at the airplane that was getting away rapidly towards freedom for the pilot and captivity for his guard.

The alighting of the S-10 in the harbor of Mahon almost accomplished what the rifle rounds of the rebels could not. The anchor that was still trailing below the seaplane touched the water first, and because of the abrupt deceleration the aircraft splashed down hard and was damaged; but the squadron of Mahon, now led by Luis Alonso Vega, had his five aircraft back. It was July 30, 1936.

At the beginning of the uprising, on July 17 1936, the other seaplanes in Majorca were the three Dornier Wal’s of the Aeronáutica Militar, which were grounded in Pollensa (on the island of Majorca) without the reduction gearboxes of their engines, removed for maintenance.

|

| April 1932: Spanish Wal, in flight over the Mediterranean |

The commander of the base (on the northern coast of Majorca) was Captain Beneito, who knew that almost all the armed forces on the island had joined the rebellion and asked for help from the Prat Naval Air Base in Barcelona, and prepared to defend the base with all the men at his disposal.

The first engagement with the rebels occurred on the 21st of July, 1936. There were casualties on both sides. The defending loyalist forces, realizing that there was no way out of the situation, and that they could not survive another assault, began to leave Pollensa a few men at a time, aboard small boats.

|

| A beautiful Spanish Wal, built in Marina di Pisa, Italy, still with her Italian registration |

Off the coast of Cape Formentor, a Dornier Wal of the Aeronáutica Militar (the air arm of the Spanish Republican Army), launched from Barcelona to aid the besieged forces, sighted the small boat with which aviation mechanic Gerardo Gil Sanchez and three other men were trying to reach Mahon. The men on the boat signaled the flying-boat to alight on the water, and when they climbed aboard they informed the aircrew that the base had fallen.

Captain Beneito and a few other men reached Barcelona with a motorboat, and a third group of the defenders of the base found refuge in the north of the island, where they would be picked up much later by a Republican submersible boat which transported them to Mahon.

|

| A Macchi M.18 is being towed by a launch, alongside a vessel of the Republican Navy, during the days of the expedition to the Balearic Islands |

The reconnaissance flights, and the missions to launch light bombs on the islands controlled by the Nationalists, began right away with the use of seaplanes, including the light Macchi M.18’s, which mainly flew liaison flights between Barcelona and Mahon, sometimes even three times a day. Every morning the aircraft dropped on Palma de Majorca freshly printed newspapers from Barcelona, and baskets of bread, still warm, that the local authorities forbade the people to gather.

|

| A Macchi M.18 seaplane. Almost all of the Spanish M.18's had folding wings. |

On the 24th of July Inca, Alcudia and Pollensa were bombed; and on the following days Palma de Majorca was hit by the S.62 and by the Dornier Wal D-1. On the 28th the Wal flew to Palma twice, the first time on a propaganda flight and the second time on a bombing mission.

|

| The Republican Wal D-1, during one of her last missions over Palma de Majorca. |

The old Macchi M.18’s got into the action on the 29th, over Palma and Son Bonet; and on the airfield of the latter they destroyed a private touring aircraft (which was probably the De Havilland DH-84 EC-TAT).

Three S.62 and the Dornier Wal D-1, with Captain Beneito aboard, took off from Barcelona on the 30th of July, to launch newspapers and flyers on the main towns of Majorca and continue on to Mahon; but over Palma, the Wal D-1 was hit by ground fire.

With the cooling system of one engine out of service, the Wal was forced to alight in a small bay of the island of Cabrera. All the attempts to keep the Wal, now with both engines out, away from the shore of the island controlled by the rebels, were frustrated by the wind that inexorably blew the seaplane towards land. Meanwhile, armed militiamen had arrived on the scene to capture the Republican crew.

With the cooling system of one engine out of service, the Wal was forced to alight in a small bay of the island of Cabrera. All the attempts to keep the Wal, now with both engines out, away from the shore of the island controlled by the rebels, were frustrated by the wind that inexorably blew the seaplane towards land. Meanwhile, armed militiamen had arrived on the scene to capture the Republican crew.

To prevent the Wal from falling into enemy hands, the crew opened the scuppers on the bottom of the vessel, and the D-1 ended its career swallowed by the Mediterranean’s waters. The day after, three S.62 searched in vain the coast of Cabrera, where the D-1 had been seen alighting for the last time; but there was no trace of the aircraft and her crew.

Captain Beneito and his mate would regain their freedom a few days later, when two submersibles from Mahon, the B-3 and the B-4, shelled the buildings occupied by the rebel soldiers, until they surrendered. Cabrera passed in the hands of the Republicans, who landed on the island a small contingent of armed sailors from the B-4 submersible boat.

|

| The Republican "Alas Rojas" in Sariñena, during the days of the expedition to the Balearic Islands. |

At the beginning of August, the bombing missions over Majorca intensified, alternating with the launch of newspapers, flyers and more propaganda material. August 5, 1936, can be considered the day the expedition to the Balearic Islands began.

A motorsailer sailed from Barcelona, with a few hundreds fighters aboard, heading for Mahon, which was to become the main base of operation. Pereira’s Macchi M.18 was in charge of patrolling the route between the Catalan capital and Minorca.

On the same day, the Navy ship Almirante Miranda took to the sea, heading for Valencia. Aboard the vessel there were Captain Bayo, charged by the Catalan government with leading the expedition, and about fifty sailors/infantrymen of the Aeronáutica Naval, who constituted the more disciplined group of the entire invasion force.

|

| Enrique Pereira Basanta |

On the 6th of August, the six S.62 of Barcelona, led by Captain Molina, flew to Valencia, from where they were tasked with the protection of the forces spearheading the invasion, ready to intervene if the latter were met with resistance.

The first landing took place on Formentera, a small island southeast of Ibiza. The invasion forces consisted of personnel of the Aeronáutica Naval, led by the Chief of Technicians Richard Iznar and by his aid Manuel Llirò, the sailors of the Almirante Miranda and Almirante Antequera, and the forces from Valencia, led by the Captain of Guardia Civil Manuel Uribarri.

Captain Bayo assumed the lead of this very heterogeneous force, in virtue of his authority as the chief of expedition forces of the Catalan Generalidad. But the contrasts between Bayo and Uribarri began right away, mainly for the strong nationalism that characterized the two men. The consequences could not have been but deleterious for the expedition, and culminated with the withdrawal of most of the forces that had come from Valencia on the 15th of August, right on the eve of the landing.

Nevertheless, at the end of the day, after the landing in Formentera was consolidated, the S.62’s seaplanes alighted in the small harbor of Cala Sabina. The crews spent the night on their aircraft, to prevent a possible coup de main, but also because suitable lodging for the men could not be found on the island.

Meanwhile, the action had also begun above the island of Ibiza. One Macchi M.18 from Barcelona launched a lot of propaganda material on the major towns of the island, to prepare the psychological terrain for the demand of surrender.

Two days later, after the besieged rebel forces on the island rejected the request, the ships Almirante Miranda and Almirante Antequera headed for Ibiza. Two miles from the coast, the Almirante Miranda sent out a launch with a few members of parliament aboard, charged with attempting to reach an agreement with the rebels and avoid bloodshed.

The crew of the S. 62 that overflew the scene saw the launch approach the dock, where a group of people seemed to be waiting; then they noted a quick reversal of course and the return of the launch to the ships, which a few minutes later opened fire. Obviously the launch had not been well received.

The six seaplanes, flown by Freire, Pelayo, Armario, Molina Pereira and Rivas launched an attack against the fortress of Ibiza, unloading all their bombs on the castle from low altitude.

The six seaplanes, flown by Freire, Pelayo, Armario, Molina Pereira and Rivas launched an attack against the fortress of Ibiza, unloading all their bombs on the castle from low altitude.

The landing on the island was postponed to the following day, August 9, in the bay of San Vicente, at about 32 nautical miles from the capital city. After overwhelming a weak resistance, the Navy infantry of Llirò and Iznar, and the militiamen from Valencia, occupied the village of San Carlos. On the evening of the same day, the S. 62’s alighted in the small harbor of Ibiza, and the aviators were housed in the fortress.

In the course of a quick inspection, to evaluate the damage inflicted by the morning bombing, Pereira realized that the damage was basically non-existent. The 26 lbs “Hispanya” bombs may have been effective against vehicles or personnel, but they were obviously useless against fortified targets.

While the events that led to the taking of Formentera and Ibiza by the Republicans were taking place, the main force, destined for the invasion of Majorca, continued to flow to Mahon. The bombing missions intensified, and struck new objectives of the island.

The omnipresent S. 62’s attacked Felanitx on August 8, Campos on the 10th and Son Cervera on the 12th. In the course of the action against Campos, the seaplane of Eduardo Guaza descended to a very low altitude to strafe an aircraft on the airfield (probably a DeHavilland touring airplane), and became the target of very violent anti-aircraft fire. The damaged Savoia seaplane was forced to alight on the water near the island of Cabrera, and reached later Mahon in tow of a submersible boat.

The 13 of August was the turn of Palma, Cabo Pera, and several important objectives on the island’s roads were bombed. On the 14th, Lluchmayor, Santañy, Felanitx and again Palma were hit. By then, the major centers of the island of Majorca had been hit by more than twenty bombings, accompanied by a hammering “psychological warfare.” On the basis of information received from people, among others, who had managed to elude the control of the Nationalists, Captain Bayo became convinced that the resistance in Majorca was near collapse.

The zone chosen for the landing was between Porto Cristo and Son Carrió, and down to Son Cervera, on the southeastern coast of the island. The choice was determined by the fact that this segment of the coast faced Minorca, and it was located at just a little more than one hour of flight time from the airbase of Mahon. The loyalists thought that the communications with the main base were going to be easier and less exposed to the enemy.

The landing operations finally began on August 16, preceded by another massive drop of propaganda material that involved almost all the pilots based in Mahon. The first to set foot on the beach of Porto Cristo were the troops of the Aeronáutica Naval.

Air cover was provided by seven S. 62’s; but Pereira’s S-5 was actually forced to alight in Valencia, after flying off-course for a compass malfunction and low visibility.

Another seaplane, the S. 62 flown by Guaza, was hit while he was flying over the combat zone. Although the pilot was severely wounded, he managed to alight on the water. The aircraft was captured by the enemy.

The landing forces began to suffer serious casualties. A few dozens sailors of the Aeronáutica Naval landed and began to march to the interior to assess the situation and gain control of the largest possible area, taking advantage of surprise. But the other landing groups stopped on the beach to reorganize, and left without protection the small vanguard of sailors, who fell in an ambush and were overwhelmed.

In the days that followed, the activity of the Republican seaplanes concentrated on the enemy movements, and on the control of the roads that led to the landing zone and the nearby villages.

Suddenly though, on the 19th of August, three unknown aircraft appeared in the sky over Majorca. They were three Italian SIAI S.55X seaplanes. Devoid of camouflage and insignia, the aircraft had been probably flown directly from Italy to the bay of Pollensa, and they engaged in action right away. Within a few hours, the S. 55X’s bombed the Republican positions (causing little damage but a lot of confusion) and the ships that shuttled between Mahon and the combat zone, including the hospital ship Marques de Comillas.

Suddenly though, on the 19th of August, three unknown aircraft appeared in the sky over Majorca. They were three Italian SIAI S.55X seaplanes. Devoid of camouflage and insignia, the aircraft had been probably flown directly from Italy to the bay of Pollensa, and they engaged in action right away. Within a few hours, the S. 55X’s bombed the Republican positions (causing little damage but a lot of confusion) and the ships that shuttled between Mahon and the combat zone, including the hospital ship Marques de Comillas.

|

| One of the three Savoia S.55X that on August 19, 1936 showed up suddenly in Majorca, to stop the landing of the Republican forces. |

A couple of days later the three Italian catamaran seaplanes were sighted in the port of Palma, by the S. 62’s. The attack was immediate. The S. 62’s of Freire (with Captain Beneito himself aboard), Molina, Rivas, Armario, Pereira, Alonso and Obradors make several single file passages at low altitude, launching bombs, grenades, and strafing the targets. All the S.55X’s were hit.

To the attackers it looked like one of them was half-sunk (and it would actually be finally destroyed on May 16, 1937), but the other two were still afloat. The following day, after having quickly fixed the damages, the S.55X’s left Majorca, never to be seen again.

The days that followed turned out to be decisive for the outcome of the Catalan expedition. The lightning-quick disappearance of the three Italian S. 55X’s, which had boosted the moral of the defenders of the island, now damped their confidence about their ability to resist for very long.

The local well-to-do people became very prodigal with money and donation of jewelry in the fund raising drives for the purchase of weapons (the drives were probably organized to galvanize the population, and give some credibility to the rumors of the arrival of reinforcements, fed also by the presence of Italian ships in the harbor of Palma); but few people actually took up arms and went fighting. Even among the rebel officers, many believed that the capitulation was near, a fact that caused frictions and led to trials and demotions.

The Republicans, however, were not able to take advantage of this state of affairs. Although it is true that the defection of Uribarri’s men had weakened the invasion forces, an equally negative effect was due to a great deal of improvisation on the part of the government forces, and to the difficulty in leading the various groups. The various units answered first to their respective leaders, very often elected (like in the case of the anarchists) regardless of any military consideration. Furthermore, during the last ten days of August bad weather limited the activity of the seaplanes of the Aeronáutica Naval, that represented the only element of superiority over the enemy, and the ammunition also began to get scarce.

The local well-to-do people became very prodigal with money and donation of jewelry in the fund raising drives for the purchase of weapons (the drives were probably organized to galvanize the population, and give some credibility to the rumors of the arrival of reinforcements, fed also by the presence of Italian ships in the harbor of Palma); but few people actually took up arms and went fighting. Even among the rebel officers, many believed that the capitulation was near, a fact that caused frictions and led to trials and demotions.

The Republicans, however, were not able to take advantage of this state of affairs. Although it is true that the defection of Uribarri’s men had weakened the invasion forces, an equally negative effect was due to a great deal of improvisation on the part of the government forces, and to the difficulty in leading the various groups. The various units answered first to their respective leaders, very often elected (like in the case of the anarchists) regardless of any military consideration. Furthermore, during the last ten days of August bad weather limited the activity of the seaplanes of the Aeronáutica Naval, that represented the only element of superiority over the enemy, and the ammunition also began to get scarce.

The tentative advance of the columns that were heading to Son Cervera and Son Carriò exhausted its thrust with the taking of the latter and the village of Son Mocho. Then the front stabilized.

On the 28th of the month the weather improved. Captain Bayo ordered the seaplanes to fly over the combat lines at low altitude to improve moral, and to alight on the water at Cala Moranda, in front of the beach of Punta Amer. The intention was to redeploy the aircraft in more direct contact with the fighting zone, and allow them to intervene more quickly.

On the 28th of the month the weather improved. Captain Bayo ordered the seaplanes to fly over the combat lines at low altitude to improve moral, and to alight on the water at Cala Moranda, in front of the beach of Punta Amer. The intention was to redeploy the aircraft in more direct contact with the fighting zone, and allow them to intervene more quickly.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Captain Bayo and to the Republican pilots, on the night of the 27th a small Italian merchantman, the Morandi, all painted black and without insignia, had unloaded on the dock of the port of Palma a few big crates, inside which there were three disassembled FIAT CR. 32 and three seaplanes Macchi M. 41 fighters.

|

| One of the Macchi M.41 seaplane-fighters that arrived in Majorca on the evening of July 27, 1936, with three FIAT CR.32's. |

Shortly after noon, while Molina, Alonso and Riva were working at their S. 62’s to prepare them for the flight, a compact and very fast biplane broke into Carla Morlanda. The men, caught by surprise, were not able to identify the airplane, but they understood right away that it was not one of theirs.

While the three seaplanes with their engines already running water-taxied quickly to take off, Pereira and Orejuela tried frantically to do the same. But they would not make it, because a few minutes later the fighter reappeared, and with a few well placed bursts of machine gun fire it riddled S-5 and S-30 with holes. No casualties were recorded among the Republican crew-members; although the men were in the water, trying frantically to swim away from the airplanes on which the enemy was ferociously firing.

When the attack was over, Pereira and Orejuela started to work immediately, trying to plug the holes in the hulls, to prevent the seaplanes from sinking. Then, with the help of the commander of the port, José Montes, they began to study the feasibility of towing the aircraft to Mahon, possibly at night, with the postal ferryboat.

That night, the news of the death of Freire reached the Punta Amer. Freire’s S.62 had taken off from Cala Morlanda with aboard Captain Beneito and a Republican fighter with a serious belly wound, who had to be flown urgently to Mahon to have surgery. The FIAT CR.32, flown by Guido Carestiato, intercepted it. (Carestiato, 1911-1980, was a famous Italian aviator and test pilot, TN).

|

A FIAT CR.32, with the colors and insignia of the early phase of the Spanish Civil War.

|

That night, the news of the death of Freire reached the Punta Amer. Freire’s S.62 had taken off from Cala Morlanda with aboard Captain Beneito and a Republican fighter with a serious belly wound, who had to be flown urgently to Mahon to have surgery. The FIAT CR.32, flown by Guido Carestiato, intercepted it. (Carestiato, 1911-1980, was a famous Italian aviator and test pilot, TN).

When the much faster FIAT caught up with the S.62, the seaplane could not evade the attack or put up any defense, because the rear guns had been removed to make room for the wounded man’s gurney.

The CR.32 toyed with its prey. The .50 caliber machine gun bullets tore into the fabric of the wings and pierced the fuselage. The wounded man was hit again, and Freire fell lifeless over the flight controls. Beneito took over, and with evasive maneuvers attempted to dodge the Italian projectiles, until the oil tank was hit, the engine seized and he was forced to alight on the water, with difficulty, at about three miles off the Cabo Pera lighthouse.

Some time later, Molina sighted the downed seaplane and, fearing the worst, alighted nearby. Helped by his mechanic, Molina was able to drag the damaged seaplane and secure it with the anchor line to the tail of his airplane. Then the unusual convoy started towards a ship that was approaching at full speed. It was the freighter “Mar Negro,” that hoisted the damaged seaplane and its crew aboard.

The 29th was another black day for the Republican forces. One CR.32 returned to Cala Morlanda and strafed again the two S.62’s that had been hauled ashore, putting them out of service for ever; while three S.81 bombers (one with the Italian civilian registration I-FAND) reached Majorca with a direct flight from Italy.

Some time later, Molina sighted the downed seaplane and, fearing the worst, alighted nearby. Helped by his mechanic, Molina was able to drag the damaged seaplane and secure it with the anchor line to the tail of his airplane. Then the unusual convoy started towards a ship that was approaching at full speed. It was the freighter “Mar Negro,” that hoisted the damaged seaplane and its crew aboard.

The 29th was another black day for the Republican forces. One CR.32 returned to Cala Morlanda and strafed again the two S.62’s that had been hauled ashore, putting them out of service for ever; while three S.81 bombers (one with the Italian civilian registration I-FAND) reached Majorca with a direct flight from Italy.

|

| The destroyed Republican Savoia S.62's, on the beach of Cala Morlanda |

From that moment on, the small but determined rebel air force that defended the island controlled the field. Captain Bayo pleaded with the Generalidad Catalana for fighter aircraft to counter the attacks of the Italian aircraft against the units that insured the provisioning from Mahon, and the ground forces which were taking heavy casualties. But neither in Catalonia nor anywhere else, there were any available aircraft capable to match the Italian fighters and bombers. The few Nieuport 52 were indispensable on the Aragonese front, and trying to counter the threat of the CR.32’s with the old Martinsyde's would have been suicide.

On September 3, the battleship Jaime l and the cruiser Libertad appeared off the lighthouse of Punta Amer. They were bringing Captain Bayo the order to withdraw within twelve hours; otherwise the fleet would not guarantee support. The end of the Catalan expedition had been decided.

The evacuation of the Republican forces from the Baleari began on September 4, in orderly fashion and with no casualties. To avoid discouraging his men, Bayo spread the voice that the objective of the operation was to attempt another landing in a location closer to Palma. All the men and almost all the weapons and material were saved.

The casualties of the entire operation, according to a September 16 communiqué of the Conselleria de Defensa, amounted to 130 dead and 115 wounded.

On September 13, 1936, after a bombing by Italian S.81’s, the rebels retook the island of Cabrera. On the 20th it was the turn of Ibiza and Formentera that had already been abandoned by the Republicans.

Very interesting altogether! Well done :)

ReplyDeleteMuchas Gracias. L.

Delete