Colonial records

New records on the Rome to Addis Ababa air route.

The historic flights of 1939.

It was the beginning of 1939, when the Milan daily newspaper “Il Popolo d’Italia” launched a race to establish a flight time record in the air route between Rome, the capital of Kingdom of Italy, and Addis Ababa, the capital of the new Italian Empire. The prize was just a commemorative plaque to celebrate the linking of the two capitals, but the goal of the initiative was to study a new civilian air route between Italy and Italian Eastern Africa.

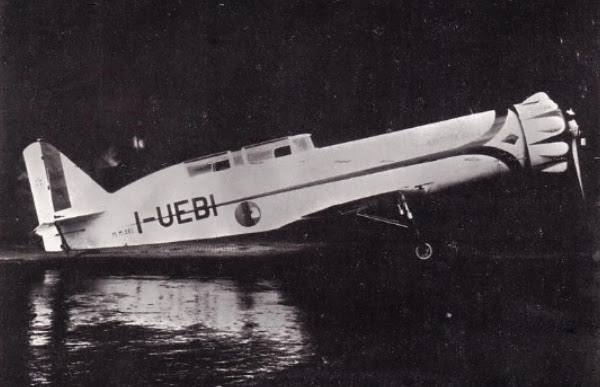

Several crews took up the challenge. The first crew consisting of Leonardo Bonzi and Giovanni Zappetta took off from Guidonia (Rome) on March 5, 1939 with a Piaggio-Nardi FN 305 monoplane tourer, specifically modified for long range flights.

This version of the aircraft, designated FN 305D and registered I-UEBI, featured a redesigned fuselage that was stretched to accommodate a larger fuel tank, and the cockpit moved astern to make room for the tank.

|

| Piaggio-Nardi FN 305 |

Powered by a 180 CV (177.4 hp) Walter Boran engine, the FN 305D covered the 2430 nautical miles distance in 18 hours and 49’, at an average speed of 130 knots, setting a record for the two-seat Category I light aircraft and won the “blue ribbon” of the air race.

The second flight was sponsored by the “Il Popolo d’Italia” and “La Stampa” newspapers, and it was made between the 6th and 7th of March 1939 by Captain Giuseppe Mazzotti, first officer Lieutenant Ettore Valenti, radio-telegraph operator Warrant Officer Silvio Pinna and flight engineer Guerrino Guerrini who was a F.I.A.T. representative. The official leader of the group was Maner Lualdi.

The aircraft chosen for the air crossing was a converted Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force) F.I.A.T. B.R. 20 bomber, with the armament removed and equipped with long range fuel tanks.

The aircraft had been designated B.R. 20L and was powered by two F.I.A.T. 1000 CV (986 hp) A80 engines, which allowed it to reach an airspeed of about 255 knots.

After several test flights, the B.R. 20L was registered I-FIAT and christened “Santo Francesco,” in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi.

The I-FIAT took off from Guidonia at 10:25 pm on March 6, 1939.

The following is Captain Mazzotti’s chronicle of the flight as he related it to Santi Corvaja, a reporter for “Il Giornale di Sicilia” newspaper, and published on July 25, 1978.

“The choice of the aircraft fell on the magnificent twin-engine B.R. 20, which was already in the squadrons of the Royal Air Force. It was a real thoroughbred designed by Dr. Rosatelli, known for his designs of proverbial sturdy aircraft.

“The airplane had been modified for the purpose. The bow machine gun turret had been removed with all the military equipment, and more capacious fuel tanks were installed to obtain have a range of more than km 5000 (2700 nautical miles).

“The two F.I.A.T. A80 engines made it possible to lift a load of about 5000 kilograms (11,000 lbs.), and the empty weight was about 4500 kilograms (9900 lbs.).

“The maximum airspeed was between 450-475 km/h (240 to 255 knots) at 13,000 feet.

“In Guidonia we loaded big bales of “La Stampa” and “Il Popolo d’Italia” newspapers that had been purposely post-dated March 7, 1939.

“We had gotten permission to fly over Egypt and the Sudan, on the condition that we followed the route Rome-Cairo-Aswan-Khartoum-Gallabat-Addis Ababa. But this path would have lengthened the flight by hundreds of miles, while the shortest orthodromic route went from Derna to Kufra (in southeastern Libya), passed Serir Nerastro and entered Ethiopia through the Ambas of the Gojjam.

“And that was the route we took, in spite of the Britons who at that time ruled Egypt. At 1:50 am on March 7, we overflew Apollonia, Cyrenaica, perfectly on schedule.

“As we proceeded into the desert, the radio became useless, due to the night effect, which creates problems with communications and radio-navigation (low frequency radio waves are reflected by the ionosphere at night, signal strength fluctuates and waves are deviated significantly, T.N.). In Rome they could hear our radio calls, but we could not receive theirs.

“It was a magical time for us aviators. We flew mile after mile in the most hermetic silence.

“Lualdi was preparing for his “officials” duties of the following day by napping on a berth, in the fuselage. The radio-operator Pinna, who was “unemployed,” also took a nap, although he remained sitting at his table.”

"Mazzotti checked the navigation chart and the stars, the compass and the altimeter. Valenti was solidly attached to the wheel. Guerrini slept with one eye closed, but both ears open to monitor the sound of the engines.

"There blew a strong Ghibli (a warm wind from the south) which slowed the ground speed of the B.R.20. It also forced the pilots to climb to a higher altitude, to preserve the filter-less engines from the impalpable sand.

"At 5:25, the airplane was abeam Wadi Halfa, Sudan, whose radio station kept transmitting its locator beam as agreed.

"At dawn, Lualdi was awakened, and Guerrini distributed some cognac around, to celebrate the crossing of the Nile. The aircraft set course for a compass heading of 176.

"The radio calls and well wishing messages began to pour in, overwhelming warrant-office Pinna; who couldn't help being annoyed even when the Duke of Aosta, the Viceroy of Ethiopia called.”

Success awaited the Italian aviators when they landed in Addis Ababa, after 11 hours and 25’, and 4575 kilometers (2470 nautical miles).

The flight etched their names in the golden annals of world records. And, of course, they also got their plaques.

During the return flight, the Britons made the Italian aviators pay for deviating from the mandated flight route. When they arrived in Cairo, they were held under house arrest in a downtown hotel. But they were soon released thanks to the intercession of the Italian ambassador Vezzolini and Libya’s governor Italo Balbo.

by Alberto Alpozzi

Comments

Post a Comment